FEAST OF SAINT PETER CHANEL, PRIEST AND MARTYR

FEAST DAY – 28th APRIL

Saint Pierre Louis Marie Chanel (Peter), was the fifth of eight children. Peter’s father was later described as a good man, but also a man “more inclined to the bottle than to religion.” Peter’s uneducated mother was a strong Christian. As a youth, Peter worked as a shepherd on their sixty-five acre family farm. Their land had recently belonged to the Church but was confiscated by the state at the beginning of the French Revolution and sold to Peter’s father.

Aware of this fact, Peter had a desire to make reparation for his family. By the end of his life he would do so, and more, by laying his life down as a priest-martyr on the tiny, remote, and barbaric island of Futuna, in the Pacific Ocean, Oceania. In the neighboring village of Cras, the parish priest, Father Jean-Marie Trompier, ran a small school for boys that Peter entered. Father Trompier taught the boys throughout the day as he went about his own duties of visiting the sick, celebrating Mass, doing chores, and conversing at meals.

Father Trompier had a profound effect upon Peter, instilling in him a desire for both the priesthood and the life of a foreign missionary. When Peter was about sixteen, he was sent to the diocesan minor seminary in Lyons and later to the major seminary in Brou. On July 15, 1827, Peter was ordained a diocesan priest at the age of twenty-four.

Father Peter was first assigned as an assistant parish priest in the town of Ambérieu. Only a few of his sermons from that assignment remain, but they show him to be a zealous and devoted preacher who carefully prepared his sermons. After a year, Father Peter approached the bishop about going on a foreign mission. Instead, the bishop assigned him to a remote parish as pastor, near the Swiss border, in the town of Crozet.

The parish in Crozet was in need. Mass attendance was low, and the previous priest had left in frustration. Father Peter spent three years showing great devotion to the sick, preaching with zeal, and organizing Eucharistic processions. By the time of his departure, he had won the hearts of the people and revived the struggling parish.

Though Father Peter was an excellent parish priest, his heart was drawn to the missions. After serving in Crozet for three years, he sought and obtained permission to enter the Society of Mary (Marists). The Marists were a newly formed order whose mission was to live as Mary did, hidden, humble, and simple. Among their charisms was to be missionaries to remote and hidden lands, especially in Oceania.

Although he had hoped to be sent on mission, Father Peter spent the next five years in the minor seminary in Belley where he taught twelve-year-old boys before becoming the spiritual director and bursar. Two years later, he was made Vice-Superior and in 1833 traveled to Rome to assist the community’s founder in gaining final approval for the society.

On February 10, 1836, the Marists were approved by Pope Gregory XVI as a Religious Congregation of the universal Church and given the responsibility of evangelizing the peoples of Western Oceania. At the age of thirty-three, Father Peter’s childhood desire came true when he was appointed as superior of a group of seven Marists (four priests and three brothers) and a newly ordained bishop who set out on a ten-month voyage by ship to Oceania. The journey was a brutal one, so much so that one of the priests died of illness along the way.

The group set sail from the port of La Havre, France, on December 24, 1836 and sailed to the Canary Islands; then south around Cape Horn to Valparaíso, Chile; west to the Gambier Islands; then to Fiji, Tongo; and eventually arrived at the small island of Futuna on November 12, 1837. Father Peter and Brother Marie-Nizier Delorme were chosen to disembark on that island.

Futuna and its neighboring island were small, being only about forty-five square miles between the two of them. The 1,000 inhabitants at the time were farmers and fishermen. The people were organized into smaller tribes who banded together into two larger kingdoms.

These two kingdoms frequently went to war with each other, one emerging as the Victors and the others as the Vanquished. They were religious people, appeasing angry gods through pagan rituals and worshiping great spirits who often spoke through the chiefs and pagan priests. In earlier years, they had even practiced cannibalism.

King Niuliki, then of the Victor tribe, at first welcomed these visitors warmly. He fed them, invited them into his home, and kept them safe. The first year on the island bore the fruit of only about ten baptisms, mostly children who were dying. The missionaries worked tirelessly at learning the local language.

Additionally, they offered Mass openly while intrigued islanders looked on, gave them farming tips, and simply showed them kindness, which was a language the Marists understood and appreciated. After a year and a half on the island, another ship carrying Marist missionaries arrived, to the delight of all.

Over the next year, the work of catechesis continued. When the king’s infant son became ill, Father Peter was given permission to baptize him. He hoped this would open the door to more converts, for he knew that if the king were to agree, everyone would be baptized and abandon their pagan rituals that Father Peter saw as demonic.

However, by the end of 1840, the king began to turn on Father Peter because more islanders were becoming catechumens. The king feared the loss of his own power, especially his pagan spiritual authority, so he withdrew his kindnesses and started to become hostile toward the Marists and catechumens. When the king heard that all the inhabitants of the nearby island of Wallis were preparing for baptism, he decided something must be done to keep this from happening on his island.

The final spark came when the king’s own son, Meitala, became a catechumen. On April 27, 1841, the king had a long talk with his son, trying to convince him to change his mind. His son refused, so King Niuliki called his son-in-law Musumusu and instructed him to kill both the catechumens and the missionaries.

The next day, after unsuccessfully trying to kill the catechumens, they went to where Father Peter was staying. First they clubbed Father Peter; then Musumusu delivered a deadly blow to his head with a hatchet. But this brutal end was only the beginning of great things to come.

Soon after, the king regretted what he had done. Many of the islanders who had grown fond of Father Peter mourned his death. This mourning and regret was turned into joy when, over the next few years, all of the inhabitants were baptized. War between the two tribes eventually ceased and peace was established. Today, those islands live their Catholic faith well and rejoice in their martyr who did more for them in death than in life.

As we honor Saint Peter Chanel, ponder the mysterious fact that the Father uses suffering and death for His glory and the salvation of souls when that suffering and death are offered to Him, sacrificially, in union with the death of His divine Son.

Ponder the incredible power of God who is able to bring good from evil, and salvation from death itself. Unite your own sufferings to Christ, and know that God wants the unyielding gift of the sacrifice of your life to be given to Him for His glory and for the salvation of souls.

PRAYER

Saint Peter, God placed the seed of desire in your heart as a youth to give yourself to His service as a missionary in far-off lands. When that desire came to fruition, you held nothing back, laying your life down sacrificially. Through that sacrifice, your blood nourished the faith of the people you served, and God transformed them into His holy people. Please pray for us, that we will courageously give of ourselves for God’s glory, no matter the cost.

Saint Peter Chanel, pray for us.

Source: mycatholiclife

************************************

ALSO CELEBRATED:

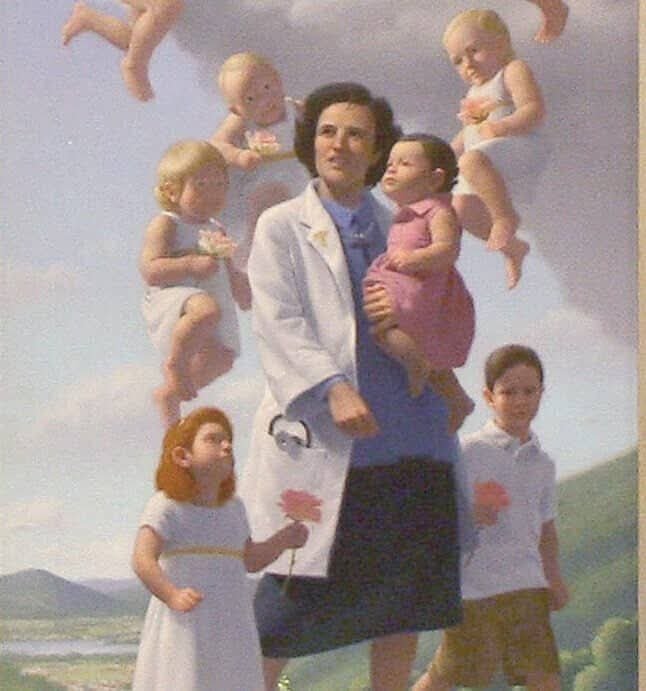

ST. GIANNA BERETTA MOLLA: A Saint for Our Times

A MOTHER WHO CHOSE LIFE FOR HER UNBORN CHILD

In less than 40 years, Gianna Beretta Molla became a pediatric physician, a wife, a mother and a saint!

Gianna Beretta Molla, born in 1922 in Magenta, Italy, was a steadfast woman, both in her beliefs and in her career.

At the age of 20, just after she graduated high school, she began studying medicine in Milan.

She instantly fell in love with the medical field and considered being a doctor a sort of “priestly mission”—not work. “Just as the priests can touch Jesus,”

Gianna once wrote on a prescription pad, “so we doctors touch Jesus in the bodies of our patients: in the poor, the young, the old and children.”

By the time Gianna met her husband, Pietro, in 1954, she was a pediatric specialist, she had obtained degrees in medicine and surgery, and she had opened a medical clinic in Mesero.

But that didn’t stop her from becoming a wife and mother.

She had three children with Pietro (Pierluigi, Maria Zita and Laura) while continuing her work as a doctor.

St. Gianna Beretta Molla is a saint for our times. But, not for the reasons many believe.

St. Gianna’s story is often portrayed as follows: she gave up her life so her child could live, thereby setting a heroic example for us of what it means to be a mother, a good mother, a godly mother.

There are many inaccurate retellings of St. Gianna’s story. In reality, St. Gianna’s story shows us someone who died to herself every day, someone who practiced that kind of self-giving love and then, when faced with a possibility of heroism, was willing to give the ultimate sacrifice, if needed.

However, St. Gianna did not die so that her child might live; and that is crucial for us to understand and remember.

Without it, we turn her story into propaganda for maternal death as the most godly and responsible choice; with correct context, we see the ways in which small, everyday choices prepare us for big ones.

In her, we see the image of a normal person—a saint who loved to ski and mountain climb, a saint who knitted, who experienced perinatal depression, who reminded her husband to give their son his suppositories, and who wrote about never having time to go to daily Mass and about watching boring reruns .

St. Gianna’s first three pregnancies were very difficult.

She experienced hyperemesis gravidarum (morning sickness to dangerous levels), long pregnancies (two that lasted 41 weeks and 3 days and one that lasted 43 weeks and 4 days), long labors (around 36 hours), and at least one forceps delivery.

After the birth of her three children, she then experienced two miscarriages.

At the beginning of her fifth, and most famous, pregnancy, she was 39 years old.

Two months into the pregnancy, Gianna was diagnosed with a uterine fibroma (a tumor which is usually benign, meaning non-cancerous, but can contribute to problems during pregnancy).

Two of the typical treatments would result in her unborn baby’s death—a surgery removing the contents of her uterus, including both the fibroma and her baby (which would have been illicit under Catholic teaching), and a surgery removing her entire uterus including its contents (which would have been licit under Catholic teaching).

Many retellings of St. Gianna’s story end here, stating that she forwent the treatment entirely and died for her baby.

That is inaccurate. St. Gianna chose the third treatment option available to her: a more cautious surgery removing the fibroma but leaving her daughter in utero (which was licit under Catholic teaching).

This surgery was generally successful, and Gianna’s condition returned to expected after it.

But she must have worried that there were more problems to come; as this rainbow pregnancy continued, she told her husband and other family members that if, at any point, anyone had to make a choice between her life and that of the baby, they should choose the baby’s.

Toward the end of her pregnancy, she went through a medical induction of labor, which was unsuccessful, and eventually gave birth through Cesarean surgery to a healthy baby girl, whom she named after herself.

After baby Gianna’s birth, things took a turn for the worse.

St. Gianna contracted septic peritonitis, a condition that involves complications of an infection of the lining of the abdomen.

This likely was caused by bacteria that entered her body during the C-section, that then spread to her bloodstream.

The infection took over her body, making her organs dysfunction, and she died a week after giving birth.

St. Gianna was not canonized for dying, nor for dying for her child.

She was canonized for her heroism in being willing to die for her child. Her death was unrelated to the life of her child. In other words, she could have been heroic and survived.

St. Gianna is not a case study of how we should eschew scientific life-prolonging treatment in favor of dying for our children.

Consider that she sought treatment for her fibroma, rather than simply allowing it to grow.

Consider that she made choices throughout her career as a doctor, fostering the health of her patients and their families.

When our takeaway from her story becomes “she’s a saint because she died for her child, and people who die for their children are similarly just meant to be saints,” we ignore her powerful intercession on behalf of maternal health.

And that is certainly intercession we need.

Today’s maternal health crisis is truly that: a crisis.

Across the world, 223 women die out of every 100,000 who give birth.

Put another way, in 2020, every two minutes, a woman died because of a condition related to pregnancy and childbirth.

Since 2016, maternal mortality rates, which were slowly decreasing, have been stalled or increasing worldwide.

This is particularly notable in the United States, which has the highest maternal mortality rate of all highly-resourced countries at 32.9 deaths for every 100,000 births.

This rate puts the U.S. in similar ranges as Uzbekistan (30 deaths per 100,000 births) and the Syrian Arab Republic (30 deaths per 100,000 births); compare this to Denmark or Turkmenistan, which has 5 deaths for every 100,000 births.

The majority of these deaths worldwide occur because of bleeding, infections, and blood pressure complications.

Sepsis, which caused St. Gianna’s death, is considered to be the primary cause of death in at least 10% of maternal deaths worldwide.

The prevention of sepsis is so important that professional organizations including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that everyone who experiences a c-section receive prophylactic antibiotics (preventative antibiotics, usually administered within 60 minutes of starting a c-section).

Yet, still, some areas do not have the resources needed to administer such antibiotics, and some providers still choose not to prescribe antibiotics in all cases when WHO or ACOG would recommend them.

Rather than facing and fighting the dangers our society accepts for pregnant and postpartum women, it can be easier to laud women’s bravery for making impossible choices.

Sometimes it feels neat and tidy to be able to put the things someone teaches us about our current lives into a box—such as, “St. Gianna placed her child’s life above her own. I am supposed to do that too if I am in that situation.” The reality of the saints is far more complicated than that.

They are often people who chose holiness in many situations and call our attention to the complex realities of injustice in our world today.

Let us not limit our retelling of St. Gianna’s story to the heroic decision of placing her child’s life above her own; let us also be reminded by our societal and global call to better care for mothers during pregnancy and postpartum.

Let us echo her compassionate care of her own patients in our care of women during the perinatal period.

She is a saint whose untimely and unnecessary death reminds us of the importance of science and high-quality medical care to our survival, and of the commitment we must have to maternal health.

Gianna was beatified by Pope St. John Paul II on April 24, 1994, and was canonized on May 16, 2004.

Her husband and four children were present at these ceremonies, making it the first time a husband had witnessed his wife’s canonization.

St. Gianna is patron of those who heroically die so that others can live.

She is patron of those experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum, long pregnancies, long labors, forceps deliveries, inductions, cesarean births, miscarriage, pregnancy at an advanced maternal age, and perinatal anxiety; those whose children are sick or need regular medications; those who knit; those who dislike watching reruns; those who die to themselves a bit every day; those let down by science and the medical system.

PRAYER

God, our Father, we praise You and we bless You because in Saint Gianna Beretta Molla You have given and made known to us a woman who witnessed the Gospel as a young person and bride, as a mother and doctor. We thank You because, through the gift of her life, we learn to accept and honour every human being.

Lord Jesus, You were for her a priviledged reference. She was able to see You in the beauty of nature. As she questioned her choice of life, she was searching for You and for the best way to serve You. Through her married love, she became a sign of Your love for the Church and for all men and women. Like You, Good Samaritan, she stopped at the side of every sick person, of the small and the weak. Following Your example, she lovingly offered up her life, while giving new life.

Holy Spirit, source of all perfection, give also to us wisdom, intelligence and courage so that, following Saint Gianna’s example and through her intercession we may serve every person in our personal, family and professional life, and thus grow in love and holiness. Amen